Gaussian noise sensitivity

Joe Neeman June 15, 2020Suppose that \(X\) and \(Y\) are positively correlated standard Gaussian vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^n\). Define the noise sensitivity of \(A \subset \mathbb{R}^n\) to be the probability that \(X \in A\) and \(Y \not \in A\). Borell proved that for any \(a \in (0,1)\), half-spaces minimize the noise sensitivity subject to the constraint \(\mathrm{Pr}(X \in A)=a\). This inequality can be seen as a strengthening of the Gaussian isoperimetric inequality: in the limit as the correlation goes to one the noise sensitivity is closely related to the surface area, because if \(X \in A\) and \(Y \not \in A\) are close together then they're probably both close to the boundary of \(A\). From a more applied point of view, Borell's inequality and its discrete relatives played a surprising and crucial role in studying hardness of approximation in theoretical computer science.

My first work on this problem concerned the rigidity and stability of Borell's inequality. Elchanan Mossel and I proved that half-spaces are the unique minimizers of noise sensitivity, and that all almost-minimizers are close to half-spaces in some sense. (Our bounds were later improved, in a special (but very important) case, by Ronen Eldan.)

With Anindya De and Elchanan Mossel, I moved onto a discrete version of Borell's inequality, known as the "majority is stablest" theorem because of its interpretation in social choice theory. We gave a short and elementary proof of the "majority is stablest" theorem. Our proof was so simple that we were also able to express (an approximate version of) as a constant-degree "sum of squares" proof, which had some implications in theoretical computer science.

ith Steven Heilman and Elchanan Mossel, I worked on the so-called "peace sign conjecture" about noise-sensitivity-minimizing partitions of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) into three parts. Unfortunately, this seems to be a hard conjecture (it's related to, but harder than, the Gaussian double-bubble problem, and we were only able to prove some negative results on an extension of the conjecture. Nevertheless, this was deemed good enough for Krzysztof Oleszkiewicz to collect on a bet, winning a bottle of vodka.

In two shorter works on Borell's inequality, I describe multivariate generalization of Borell's inequality, and I explore in greater detail the relationship between Borell's inequality and the Gaussian isoperimetric inequality.

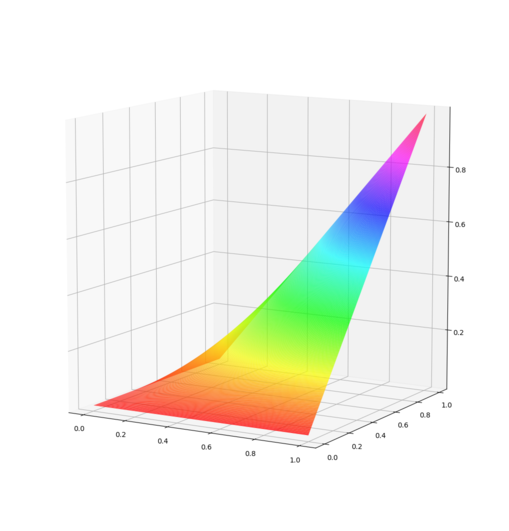

One common feature of most of the results above is that they are linked to a new notion of not-quite-convexity: we say that a twice differentiable function \(f: \mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}\) is \(\rho\)-convex (where \(\rho\) is a parameter between zero and one) if $$\begin{pmatrix} f_{xx} & \rho f_{xy} \ \rho f_{xy} & f_{yy} \end{pmatrix}$$ is a positive semi-definite matrix at every point. The crucial thing about \(\rho\)-convex functions is that they satisfy a certain Jensen-type inequality for correlated Gaussians: \(f\) is \(\rho\)-convex if and only if for any functions \(g\) and \(h\), $$\mathbb{E} f(g(X), h(Y)) \ge f(\mathbb{E} g(X), \mathbb{E} h(Y)),$$ where the expectation is with respect to \(\rho\)-correlated Gaussian variables \(X\) and \(Y.\) This is actually very easy to prove, and it turns out to be quite useful. For example, Borell's inequality is just the fact that the \(\rho\)-correlated Gaussian copula is \(\rho\)-concave.